Clinical relevance of the placebo and nocebo phenomenon

Numerous studies have confirmed the substantial positive effects that are due to treatment-unspecific factors, which are classically referred to as placebo effects. This has been demonstrated for a variety of conditions including hypertension, depression, coughing in viral infections, functional disorders, bipolar mania, schizophrenia, neuropathic pain, migraine, fatigue in cancer patients and others (de la Cruz, Hui, Parsons & Bruera, 2010; Enck & Klosterhalfen, 2005; Lee et al., 2005; Macedo, Banos & Farre, 2008; Preston, Materson, Reda & Williams, 2000; Quessy & Rowbotham, 2008; Rief et al., 2009a; Sysko & Walsh, 2007). Strong treatment-unspecific effects have also been reported with interventions using sham surgery procedures, e.g., in osteoarthritis during arthroscopy (Haynes, Moseley & McGowan, 1975), during intracranial stem cell injection in Parkinson's disease (McRae, Budney & Brady, 2003), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in depression 13 (Brunoni, Lopes, Kaptchuk & Fregni, 2009), or during migraine treatment using acupuncture (Linde et al., 2005). Contrary to earlier assumptions, placebo treatment may have long-term effects (Quessy & Rowbotham, 2008). In the cited surgery studies, patients who believed that they received "real" surgery improved the most, irrespective of the actual treatment they were given. Similarly, in a study on survivors of myocardial infarction, poor medication adherence was associated with a higher risk of mortality (Horwitz et al., 1990), irrespective of whether the active compound or a placebo was taken, and regardless of other potential risk factors. This has been attributed to the greater expectancies or beliefs, both in drug and placebo responders that the medication may be of help.

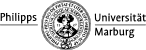

Even for everyday medical interventions such as local anesthetic skin injections, doctor‘s instructions about anticipated effects determine the level of pain that the patient perceives (Varelmann, Pancaro, Cappiello & Camann, 2010). 140 women (healthy parturients at term) requesting labor epidural anesthesia or presenting for elective cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia participated in this study. The patients has been divided in two groups, which differed in the information the patients were given before they received the injection. Group 1 was given the following warning before the injection: “You will feel a big bee sting; this is the worst part.” Group 2 received the following information before the injection: We are going to give you a local anesthetic that will numb the area and you will be comfortable during the procedure.” Compared to Group 1 patients in Group 2 indicated significant less pain sensation (see figure beyond). The doctors warning have influenced the patients expectations and with it the followed pain sensation.

Even for everyday medical interventions such as local anesthetic skin injections, doctor‘s instructions about anticipated effects determine the level of pain that the patient perceives (Varelmann, Pancaro, Cappiello & Camann, 2010). 140 women (healthy parturients at term) requesting labor epidural anesthesia or presenting for elective cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia participated in this study. The patients has been divided in two groups, which differed in the information the patients were given before they received the injection. Group 1 was given the following warning before the injection: “You will feel a big bee sting; this is the worst part.” Group 2 received the following information before the injection: We are going to give you a local anesthetic that will numb the area and you will be comfortable during the procedure.” Compared to Group 1 patients in Group 2 indicated significant less pain sensation (see figure beyond). The doctors warning have influenced the patients expectations and with it the followed pain sensation.

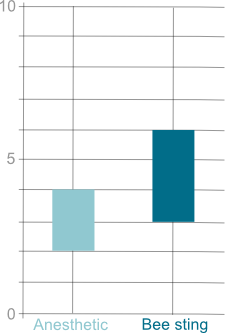

Along these lines it has been shown that the expectation that an analgesic is expensive increases its efficacy compared to pills considered being cheap (Waber, Shiv, Carmon & Ariely, 2008). Similarly, hidden application of pain medication is associated with a substantial decrease in analgesic efficacy compared to open application, where the patient is aware of the treatment being administered (Benedetti et al., 2006). The analgesic effect of a drug reduced, when patients received the drug hidden, e.g. an injection via a computer, so that they didn’t know if and when they received the medicament. In contrast to this condition, the patients receiving open injections knew, if and when they received the drug. It was shown that through the knowledge of having received the drug, that the analgesic effect in the context of an open injection was bigger than the effect in the condition hidden injection. This effect can be attributed to unspecific psychological treatment factors, like the patient’s expectation of a pain reduction after having received the drug.

Along these lines it has been shown that the expectation that an analgesic is expensive increases its efficacy compared to pills considered being cheap (Waber, Shiv, Carmon & Ariely, 2008). Similarly, hidden application of pain medication is associated with a substantial decrease in analgesic efficacy compared to open application, where the patient is aware of the treatment being administered (Benedetti et al., 2006). The analgesic effect of a drug reduced, when patients received the drug hidden, e.g. an injection via a computer, so that they didn’t know if and when they received the medicament. In contrast to this condition, the patients receiving open injections knew, if and when they received the drug. It was shown that through the knowledge of having received the drug, that the analgesic effect in the context of an open injection was bigger than the effect in the condition hidden injection. This effect can be attributed to unspecific psychological treatment factors, like the patient’s expectation of a pain reduction after having received the drug.

In fact, eliminating positive expectations about pain-relieving effects of drugs resulted in 50% increases of medication doses to achieve the same effect as with positive expectations; some empirically well-validated drugs (such as proglumide) lost their efficacy completely when positive expectations were eliminated (Finniss, Kaptchuk, Miller & Benedetti, 2010). This shows that health care costs would dramatically increase if placebo effects were eliminated. Expectations of patients about drugs substantially influence the amount of medication needed. This again underlines the health economic dimension of expectation and conditioning.

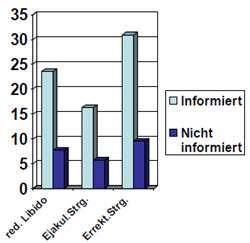

In many medical conditions, patients in the placebo arm of a study reported side effect profiles comparable to patients in the drug group, and many discontinued treatment because of side effects although they received a placebo pill (Preston, Materson, Reda & Williams, 2000; Rief, Avorn & Barsky, 2006; The-Treatment-of-Mild-Hypertension-Research-Group, 1991). If cancer patients believe to receive a new drug, 71% of them develop at least 2 new symptoms, even if they are in the placebo group (de la Cruz, Hui, Parsons & Bruera, 2010). Similar phenomena have been shown for healthy volunteers receiving placebo pills in drug trials (Rosenzweig, Brohier & Zipfel, 1993). These nocebo effects seem to be related to the individuals‘ beliefs and expectations: When patients are informed that an urological drug (Finasteride) induces sexual dysfunction, the prevalence of this symptom increases by a factor of three (Mondaini et al., 2007). 120 patients with benign prostate hypertrophy participated in this study. All subjects were treated with Finasteride.  The patients have been divided in two groups, which differed in information given in the context of the treatment. One group was pointed out that sexual dysfunction could be a side effect of the drug. Patients in the second group did not receive any further information. It could be shown the patients in the informed condition named significant more often the experience of sexual dysfunctions (see figure).

The patients have been divided in two groups, which differed in information given in the context of the treatment. One group was pointed out that sexual dysfunction could be a side effect of the drug. Patients in the second group did not receive any further information. It could be shown the patients in the informed condition named significant more often the experience of sexual dysfunctions (see figure).

Comparable results were found for β-blockers (Cocco, 2009). Even more general drug-associated expectations determine side effect profiles. Patients who expected the side effect profile of tricyclic antidepressants reported more side effects than when expecting the side effect profile of SSRIs, although they received placebo pills in both conditions (Rief et al., 2009b). Similarly, patients of placebo groups in migraine trials reported different side effect profiles depending on whether they expected to receive anticonvulsants, triptans, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Amanzio, Corazzini, Vase & Benedetti, 2009). Therefore, the manipulation of patients‘ expectations can result in negative effects, but expectation manipulation can also be used for the benefit of treatment outcome.